HIROSHIMA memory keepers Succeed to history

Vol. 4 2015.7.10 up

As a person living in Hiroshima, I would like to convey my hope for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

Yumie Hirano

An A-bomb Legacy Successor

What do people handing down the experience of the A-bombing think and try to convey?

Ms. Hirano has given presentations in various countries, including the U.S., and she is one of the first A-bomb Legacy Successors from the Hiroshima City training program.

We asked her about what made her start her peace activities and her experience overseas.

Section

What made her start her activities overseas?

Ms. Hirano, you are conveying what happened in Hiroshima to people overseas. What made you start doing this?

I taught Japanese to foreign people for ten years. Also, as a volunteer guide from SGG, a goodwill guides’ group, I showed foreign tourists around Miyajima and other tourist spots.

* Systematized Goodwill Guides (SGG) is “a small kindness campaign,” in which members assist overseas visitors so that they can enjoy traveling around Japan without the inconvenience of language barriers. It is registered with the JNTO, the Japan National Tourism Organization.

Since there were many foreign visitors who were interested in the A-bombing on Hiroshima, I sent some materials about the A-bombing to them after the tour, and I also started learning about it.

Rather than being involved in a “peace activity,” I wanted to tell about the A-bombing and convey my hope for the abolition of nuclear weapons as a person living in Hiroshima.

I heard that you also gave presentations in various countries, such as the U.S., Peru, Mongolia and so on.

Yes. My presentation in Mongolia was arranged by a Japanese language teacher there. Learning about peace is common in Mongolia, and many people seriously listened to my presentation.

There is a large organization called the “Never Again Campaign.”

It was established about 30 years ago, and I joined its activities for two months in 2011, as its tenth graduating member.

We are not allowed to talk only about the A-bombing in the U.S. and can only get approval to talk about it if we also introduce Japanese culture.

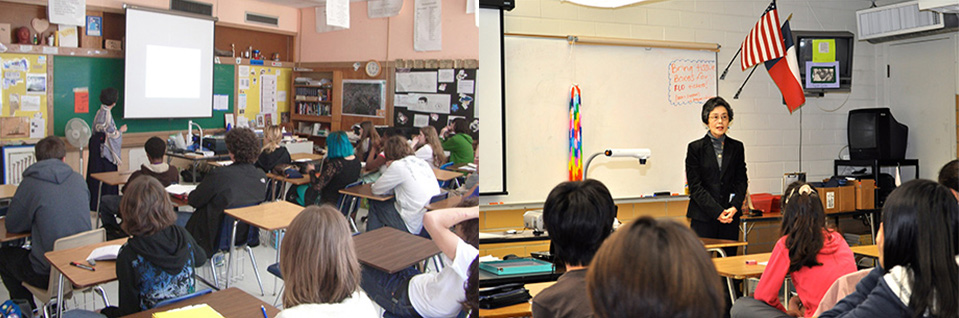

Since I had been learning tea ceremony and calligraphy, my husband recommended that I join that activity. I gave presentations to various people, from kindergarteners to adults, visiting churches and schools in the U.S.

The U.S. is the country which dropped the atomic bomb. What were people’s responses?

I remember very well the presentation I gave at a school in Austin, Texas, which is said to be conservative. Lectures about the A-bomb were rarely held in Texas in those days. In Austin, there were some people who supported the NAC. I stayed at their houses to give presentations. We chose the places for the presentation by exchanging emails in advance and through the information my host friends had given.

Although Texas was said to be conservative, Austin, the state capital, was a town of many colleges and more open-minded. In the social studies curriculum in the U.S., students usually study about the world wars in February to March. When I visited the school, they had just finished the chapter which said the A-bombing had brought the war to an earlier end.

In that school, some students, sitting with their feet up on their desks, didn’t listen to me at first. However, when I said, “I came here to tell what happened under the mushroom cloud,” their attitudes changed and they started to listen.

I can imagine that you made all kinds of efforts to speak to a wide age range of people.

I tried various things, like changing the content of my presentation from school to school.

In one school, I was going to use picture cards, but they didn’t allow me to use one card in which a mother holding her child was frantically trying to escape the fire. I protested, saying, “Students cannot learn what really happened without this card!”

I also showed students pictures of the scenes after the A-bombing. I had them imagine what they would think if something like this happened to their families.

Did you get some comments after the presentations?

Yes. I have kept them even today.

One of them from an elementary student reads, “If I became president after I study hard, I would never drop an A-bomb.” Another was, “I am sorry” written in Japanese from a student who had been studying Japanese. When I read them, I was close to tears.

About her activities as an A-bomb Legacy Successor

I heard that you are one of the first A-bomb Legacy Successors in the Hiroshima City training program. Why did you participate in it?

At first, I hesitated to participate in it. I thought only A-bomb survivors could convey what happened at the time of the A-bombing.

My family was not affected by the A-bombing. Immediately after the end of the war, they came back to Hiroshima from Shanghai, and my mother was pregnant with me at that time.

Although I was involved in the NAC activities, I didn’t think that my knowledge about the A-bombing was enough. I wanted to learn more and tell as many people as possible about it, so I applied for the project.

What did you do in the training sessions?

We had an intensive program with two 120-minute classes per day to learn basic knowledge, like the effects of the A-bombing. It took about three years to become an A-bomb Legacy Successor.

We also had a class in which we listened to about 30 survivors. Then, each trainee chose one survivor and took over his/her experience.

You took over some other person’s experience and convey it to others, didn’t you?

Yes. There is an opinion that if this training program had started ten years ago, we could have taken over their experience more accurately. I am one of those who agree with that. Now, most survivors who tell their stories were around ten years old at the time of the A-bombing, on August 6, 1945.

Ten years ago, there were many survivors who were in their 20’s at that time, but we have only a few now. Still, some of the survivors in their 90’s, who have vivid memories about the A-bombing, are telling their stories.

If there is something difficult in conveying the A-bomb experience, could you tell us?

I have many. For example, if a survivor says, “I saw a woman melting by heat rays just in front of me,” that is correct as his/her memory. However, it is scientifically impossible that a human body melts by heat rays in a few seconds. An A-bomb legacy successor who takes over his/her experience has to avoid the expressions like “melting.” That is oemne of the hard parts.

Message to the younger generation

Thank you for your interesting talk. Finally, could you give some advice about what we, the younger generation, can do?

In order for the younger generation to convey the A-bombing on Hiroshima, you should free yourself from the ambiguous word, “peace” and try to find a way to use something visible and concrete, not ideological. Look at the monuments, A-bombed buildings and trees in Hiroshima, feel them and think. That is one of the ways you can start. I hope you can find your own answers and convey them to others.

Interviewed on May 2015.

About

"Interviews with HIROSHIMA memory keepers" is a part of project that Hiroshima「」– 3rd Generation Exhibition: Succeeding to History

We have recorded interviews with A-bomb survivors, A-bomb Legacy Successors, and peace volunteers since 2015.

What are Hiroshima memory keepers feeling now, and what are they trying to pass on?

What can we learn from the bombing of Hiroshima? What messages can we convey to the next generation? Please share your ideas.