HIROSHIMA memory keepers Pass down a story

Vol. 10 2017.7.28 up

There were about 2,000 children who didn’t survive, even though they weren’t exposed to the A-bombing. I decided to be a storyteller to let people know what real war was like for them.

Syouso Kawamoto

A-bomb survivor

What do people handing down the experience of the A-bombing think and try to convey?

Mr. Shoso Kawamoto’s (83) parents and siblings were killed in the A-bombing, and he has lived as an orphan.

He tells us that he once was one of the street-orphans, was addicted to gambling and easily got into fighting when young, but later he pulled himself up by remembering his mother’s words.

Section

Beginning to tell his story

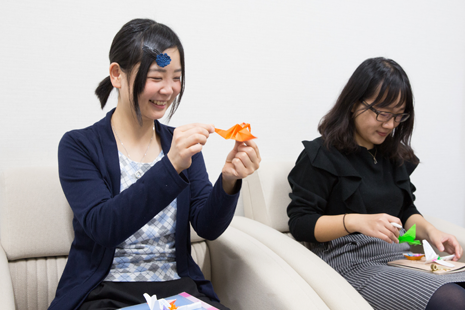

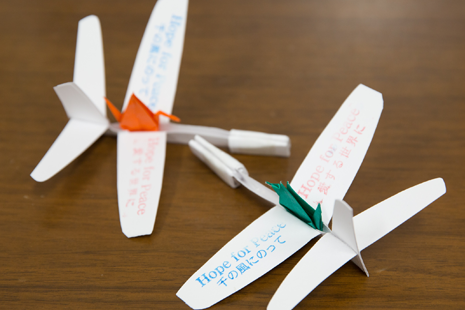

You have a lot of paper cranes now. Did you fold them all by yourself?

Yes. I have folded about 200,000 cranes so far. Children are very happy when given one.

Also,these cranes put a smile on faces of foreigners who visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, and we can get acquainted with each other. I can’t speak English, though.

200,000 cranes!! That’s an incredible number! When did you start folding cranes?

I started folding cranes at the time I became a volunteer storyteller eight years ago.

I wanted children from all over the world to take one to their country with them, together with the souls of the children who died in the A-bombing.

I wished those children who died could have played cheerfully. I wanted them to visit various places.

But since it is impossible, I wanted the foreign children to play with the cranes.

That was the only reason I started.

What made you start telling your experience?

I moved back to Hiroshima after living in Okayama for 30 years.

When I participated in a singing contest, a volunteer in the steering committee asked me if I could tell the story of A-bomb orphans. Emiko Okada, another storyteller was also at the venue where I spoke.

She said that my story should be heard by many people. She said, “Why don’t you become a storyteller and work with me?” That was the start.

Now the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is under innovation, but when I visited the former museum, I saw few pictures of A-bomb orphans. It only mentioned, “2,000 to 6,000 orphans were missing.”

When I saw this description, I wanted people to know what difficult lives the orphans had.

There were about 2,000 children who didn’t survive, even though they weren’t exposed to the A-bombing.

No one knows that there were children who starved to death. I decided to be a storyteller to let people know what real war was like for them.

Had you ever told your experience before you became a storyteller?

No. I just talked about it with my friends. I had never been asked to tell it, nor had I ever voluntarily told anyone that I was an A-bomb survivor.

About August 6

Were you born and grown up in Hiroshima?

Yes. I lived in Ote-machi (former Shioya-cho). Our house was located across from the former Bank of Japan.

How old were you at the time of the A-bombing?

I was a sixth grader of Fukuromachi Elementary School.

As air-raids by American bombers intensified, the government decided to evacuate elementary school children to rural areas. Children at our school were evacuated to four villages in the outlying areas.

I was taken to Kamisugi-mura, Futami-gun (present Miyoshi City) in April, and was there until August 9.

We stayed at a temple and went to school there every day.

We were a group of about 80 boys and girls, and at first we enjoyed living with our friends. For a while at the beginning, we created a big disturbance.

Since it was such a rural area where no sound was heard, some third and fourth graders started crying, wanting to see their mothers.

You were far away from Hiroshima on August 6. Do you remember anything about what happened on the day?

We were cultivating unused land, planting sweet potatoes before going to school that morning.

Then, we saw a white cloud rising and spreading in the direction of Hiroshima City. We said to each other, “What is that cloud?”

We didn’t hear any sound. All we saw was a growing white cloud. We were stunned, saying, “What a gigantic cloud!” At around 6 o’clock in the evening, we heard that the entire city of Hiroshima had been destroyed.

How did you feel when you heard that?

I felt uneasy because I had no idea what had happened.

From the next evening, family members came to pick their children up. I asked them what happened in Hiroshima. When a young man living near my house came, I asked, “How is my home?” He just shook his head, saying nothing.

On August 9, my sister by five years came to pick me up.

She worked for the management bureau at Hiroshima Station then. She looked fine although she had some bruises. I was so happy to see her that I burst into tears.

Did she come by train?

Yes. The Geibi Line resumed its service on August 7.

She told me that our mother, younger sister and brother had been burned to death, holding onto each other in the house.

She said that she had been able to find the three, but she didn’t know where our father and our eighth-grade sister were.

She also said that she had asked a soldier working on the rescue operation nearby to cremate the bodies, and she collected their ashes.

Did you return to Hiroshima with your sister after that?

Yes. We took the Geibi Line to a station near Hiroshima Station and walked into the city.

There was nothing! There was absolutely nothing left!

My sister and I walked to a first-aid station to look for our father and sister. The station looked like a burned auditorium, and smelled bad. There were wounded people lying on straw mats. We walked around avoiding those people, saying, “Does anyone know Michiko Kawamoto?” “Is Michiko Kawamoto here?” We searched a lot of aid stations for three days in vain. I became sick and said to my sister that I couldn’t continue any more. After that, she kept searching without me. After all, we couldn’t find them.

A-bomb orphans

You and your sister were left alone, weren’t you? How was your life after that?

My uncle, my mother’s brother, survived and was the chief of the Welfare Department at City Hall. He was in charge of building shacks for people in rescue operations. He let us live in one of them temporarily. Those shacks were made of materials including tin plates collected from debris. We were there until the time around the Makurazaki Typhoon in September, and moved to a room at Hiroshima Station where my sister worked. The room had been used as a break room for the employees and was separated by a partition into halves, and we rented one half.

What happened to the evacuated children like you, coming back to the city after August 6?

I was lucky enough to have my sister alive, but the number of the children who lost all their family members was estimated to be about 2,700. They were first taken to City Hall, however, there were too many orphans to take care of. The city provided orphanages for only about 700 children. The rest of the orphans were made to go away.

There were no places to accommodate them. So many children lived under bridges, together with adults who had lost their houses at the A-bombing. Many of those children and adults, however, were washed away when the Makurazaki Typhoon hit Hiroshima on September 17.

The children surviving the typhoon started to live on the streets around Hiroshima Station. Those children also died of the cold and starvation one by one, and it is said that the death toll was about 1,000 by the end of the year. Also, after the turn of the year, the number of orphans was gradually increasing because many children who once had been under their relatives’ custody were driven out of their houses.

Tell me about how those children were living on the streets.

First of all, they had nothing to eat. After the Makurazaki Typhoon, soup-kitchens started, but only 500-600 bowls of sweet potato porridge were provided. Children who were not able to get any soaked their towels in the soup left in the bottom of the pots, and sucked it to a last drop. Soup kitchens were open only twice a week, not every day. They stopped their service in October or November. After that, orphans died one by one.

Their bodies were thrown into dumps and burned with garbage.

There was no place to bury them. They were treated just like things, not human beings.

Street orphans even ate newspapers which had been thrown away after being read in the morning.

There was no grass growing then. So, it was the only thing that was soft enough to chew. Children fought for a piece of newspaper. They swallowed it with water, and then they died. Little is known about those children.

How long did such situation last?

It lasted for some time. After the typhoon, yakuza, gangsters, took care of those children. They provided the children with shoeshine kits. They also made the children collect iron scraps in the ruins and cigarette butts at the station, which could be converted to cash. The gangsters collected vegetables at stalls, and made the children cook porridge with them, and sell it at five yen a bowl. I saw the children share the leftovers. But then, a lot of black markets were built in front of the station, so the children couldn’t do their business anymore. Gangsters were busy cracking down on the stalls and the children were left uncontrolled. So, the children made groups of 5-6, and attacked the stalls.

Do you mean they robbed?

Yes. Their first target was food stalls. They got into a stall and said, “Give us udon noodles!” or “Give us some bread!” If they didn’t give them any, they would go on a rampage and break the stall. When they were two or three children, shop owners sometimes gave them something to eat, but if they repeated it, they were made to go away.

Then, the reconstruction projects, such as building bridges, started. Hiroshima City hired yakuza as supervisors on sites.

Street orphans were used as recruiters.

When was that?

It probably was in 1946. They were hired at 100 yen a day.

Peace, in the true sense of term, didn’t come until 25 years after the A-bombing.

There are few records left about the first ten years of Hiroshima after the end of the war.

Hiroshima was like a city of yakuza. There were few people who could lead ordinary lives.

Twenty-five years after the end of the war, a law controlling gangsters was finally enforced, and consequently, the police cracked down on them. I think that was the start of the restoration of Hiroshima.

When they hear the name of Hiroshima, many people may imagine a city of yakuza in the movies, right?

Many of those movies featured violent scenes between gangsters. But it was not such an easy thing.

Gangsters carried a kitchen knife or a gun with them, or sometimes they beat each other with clubs.

They didn’t stop fighting until the other person didn’t move. Otherwise, when the enemy got up, they got beaten twice as much. They had learned the way to fight.

It was such times. That’s why there are not so many people who can talk about the restoration time of Hiroshima.

The first gangsters who came to Hiroshima in those early days were taught to be chivalrous in some sense and never fight against common people. However, after the street children, who had never been educated in the way of gangs, joined them, their way of justice was completely ignored.

Drugs became raging. The children became addicted to philopon, a kind of methamphetamine, while they sold it. That was really scary. Suddenly, many children went on a rampage.

Hiroshima has such a history before it became what it is today, doesn’t it?

Everyone in those days thought about how to make a living for the day.

Shacks were being built here and there. Everyone was desperate to live.

When they saw someone who had something to eat, they knocked him down and took away the food for themselves.

That was not because they hated the other persons, but because they needed to survive.

Repetitive gambling and fighting when young

How did you make a living until you were old enough?

My sister died of leukemia right before I became 11 years old.

My uncle came to take me in. He soon tried to put me in an orphanage, but all the orphanages were full. When my uncle and a city officer were arguing, Mr. Kawanaka, the mayor of Tomo Village, offered to take care of me. So, I started working for Kawanaka Soy Sauce.

Did you start working when you were 11?

Yes. He ran a soy sauce factory and in his spare time, grew vegetables as well as kept cows.

He told me that if I worked hard, he would build a house for me someday. I believed his words and worked hard. I wasn’t paid at all because I was 11. Anyway, I was satisfied with having something to eat. I could eat to the full.

At the age of 18, I joined the local youth association and became its leader at age 20.

When I was 23, Mr. Kawanaka built a house for me as he had promised. Then I fell in love with a girl in the association. I wanted to marry her and went to see her parents.

Her parents opposed our marriage, saying, “You were in Hiroshima at that time, weren’t you? Those who were there then were contaminated with radiation. If you marry our daughter, she will give birth to a deformed baby.”

This made me angry. I couldn’t believe that the reason they refused our marriage was such a thing.

I had worked hard and had a house, but there was no point having my own house if I couldn’t get married.

I decided to live alone from then on. I thought I didn’t need any help from others. I left the village for Hiroshima City.

Didn’t you fall in love with anybody after that?

I had a lot of bigger issues than love. I became a member of yakuza. I was able to get a job at a small delivery company because I had a driver’s license. However, I was easily tempted by young gangsters to gambling on pay days. Also, I was frequently asked to help whenever there was a fight, given a bamboo club. They said to me, “Hit! Hit!”

I had no friends besides them. All the orphans like me were in the same boat.

In those days, hospitals bought blood at 1,200 yen per two 200cc bottles. I could eat for ten days for that amount. So I would sell my blood once a month and hang around. When I wanted, I worked. That was what my life was like then.

His mother’s words and his message to the future generation

When I was 30 years old, I couldn’t pay the fine for a traffic violation and had my driver’s license confiscated. That stopped me from continuing my job as a driver, and I lost the meaning in my life. I got on a train to look for the place where I could kill myself and got off at Okayama Station. I happened to see a help-wanted poster in front of an udon noodle restaurant. It read, “Wanted: Live-in help.” The moment I saw it, my mother’s words came up to my mind.

Could you tell me her words?

“You can do it if you try! If you can’t do it, that’s because you give it up on the way. Don’t give up!”

I decided to start a new life again if the restaurant hired me, although I had no experience to make udon. That was the start of my second life. I worked hard there for three years and later worked at the employees’ dining room at Tenmaya Department Store for five years. Then, four friends of mine and I set up a company which sold boxed lunches and ready-made dishes wholesale to supermarkets. At the age of 50, I became independent and had my own company in the Mizushima area. I worked as the president for 10 years and came back to Hiroshima at age 70.

I have a feeling that you have gone through various experiences. Do you have a message to pass down to the next generation and us?

I want children to have power to protect themselves. Education is the key.

I think their fathers and mothers, too, need to educate them face-to-face.

Now people talk or text message on their phones, but it is very important to talk with each other face-to-face and know each other well.

Luckily, I was able to find a full-time job. However, quite a few orphans couldn’t. They only got day jobs. They can work until 70 years old, but can’t when they become around 80. They didn’t pay for health insurance, and they don’t get a pension. They are in and out of prison for a better life, repeating theft. They are provided meals and baths there. How can they live on welfare?

I don’t want children to follow the example of those people. I want parents to have opportunities to talk sincerely with their children about their futures. It is very important for them to listen to others so that they can know what they should believe or what is true.

I want them to have such opportunities. Today, we can do what we want.

Thank you very much.

Interviewed on June 2017.

About

"Interviews with HIROSHIMA memory keepers" is a part of project that Hiroshima「」– 3rd Generation Exhibition: Succeeding to History

We have recorded interviews with A-bomb survivors, A-bomb Legacy Successors, and peace volunteers since 2015.

What are Hiroshima memory keepers feeling now, and what are they trying to pass on?

What can we learn from the bombing of Hiroshima? What messages can we convey to the next generation? Please share your ideas.