HIROSHIMA memory keepers Pass down a story

Vol. 9 2017.7.27 up

I have been grateful to those foreign students from the bottom of my heart. They always helped and supported us. We were comforted and encouraged by them.

Meiko Kurihara

A-bomb survivor

There are people who have committed themselves to passing down the A-bomb survivors’ experiences to the next generation. What do they think about and try to share?

Meiko Kurihara, 91, spent a week, August 7 to 14, just after the A-bombing on Hiroshima, with foreign students from Asian countries on the grounds of Hiroshima University of Arts and Science. She told us what Hiroshima was like then and how she spent days with them.

Section

About the day, August 6

Would you tell me how old you were at the time of the A-bombing?

I was nineteen years old.

Our house was located in Otemachi 7-chome, about 900 meters from the hypocenter.

We were a family of four, but only my father and I were living there then.

My mother and my younger sister had evacuated to a rural town where our family friend lived. My sister was such a coward that once an air raid alert sounded, she would take cover in the closet and wouldn’t come out.

I hear you spent some time with some foreign students after the A-bombing. Had you known them before?

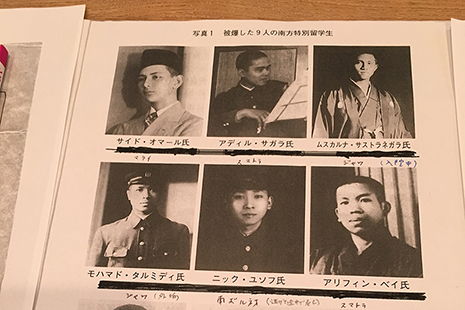

Yes. There were nine foreign students from different countries, such as the Philippines, Burma and China.

Five of them came to Hiroshima in 1943 and four in 1944. They were going to return to their home countries after finishing studying at Hiroshima University of Arts and Science.

The dormitory called Konan-ryo, where they were living, was in Ote-machi 8-chome, close to my home. My home was on the north side of the nearby bridge, Yorozuyo Bridge, and their dormitory was on the south side.

I often saw them on the street. But I never talked to them because in those days girls were not supposed to walk or have a conversation with boys.

So, I didn’t have the slightest idea that I would wind up spending some time with them after the A-bombing.

Where were you on August 6?

I was a college student but was mobilized to work at a factory in Mukainada, about six kilometers away from the hypocenter, working as a lathe operator.

When the A-bomb was dropped, the ceiling of the factory was blown away and window glass was broken into pieces. I caught glass splinters in my fingers. At first, I thought a machine had exploded.

I had never seen such a weird cloud before. The bottom of the cloud was white partly mixed with black and the upper part of it was shining pink.

I understand your home was very close to the hypocenter. Did you return to your house after the A-bombing?

I couldn’t enter the central area of the city, which was a sea of fire that day. So, in the early morning, before dawn of the following day, August 7, I went back to search for my father. When I entered the central part of the city, I saw many smoldering remains of fire. The city I saw from near Hiroshima Station was a stretch of nothing.

I am a Christian, so I kept praying, “May God help us.”

There were dead bodies and injured people lying everywhere, and I had to step over some of them.

In an ordinary situation, I would never step over a dead or an injured person. I must have been driven insane.

I walked with the prominent stone gate as a guide to reach our house, but I couldn’t find my father there.

My father was a medical doctor. I thought that he could be somewhere at a first-aid station helping injured people. So, with a charred wood stick, I left a message, saying, “I am all right. Meiko,” on the front side of our house’s fireproof water tank which was made of concrete.

Then, I went to the Japan Red Cross Hospital and searched for my father there. Some of the people there had their intestines hanging out, and some had lost their eyeballs. I frantically looked for my father, but couldn’t find him there.

Later I was informed that my father was dead. He was teaching health nurses at Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital at the time of the A-bombing and got buried under the beams of the building.

A nurse standing by him tried to pull him out, but he said to her, “You should go now. If you see my family, please tell them to take care of everything.” Those were his last words before he was engulfed in flames.

I couldn’t find my father and had no place to be. I was totally at a loss, when I came across one of my seniors at school in front of Hiroshima University of Arts and Science. I was overjoyed. We threw ourselves into each other’s arms and cried.

I told her that I had no place to stay that night. She kindly invited me to join her, saying, “I am with friends in the schoolyard of Hiroshima University of Arts and Science.”

I met the foreign students there.

About the days I spent with the foreign students

I think few people know that there were some foreign students in Hiroshima on August 6.

The foreign students told me that, at the time of the A-bombing, some of them were at school and the others were in the dormitory. On seeing fire coming toward them, those foreign students in the dormitory fled to the nearby river and found some 30 school girls crouching on the river bank. They went into the river, put those girls on two makeshift floats, and pushed the floats in the river to escape the fire together.

They said they had been frantic, but the spreading fire gradually covered the surface of the river, and the girls were swept away from their floats one after another, leaving with screams. The students said it was heartbreaking.

I heard that neighbors of the dormitory had assisted those foreign students, bringing them some food.

Because of such interaction, the foreign students helped Japanese people quite naturally in that unprecedented situation, didn’t they?

I suppose so. While sleeping outside together, they encouraged us although we Japanese people should have comforted them.

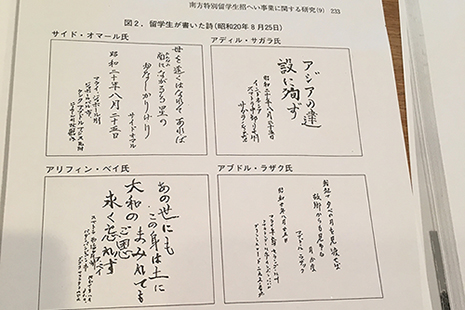

They played their national folksongs, Bengawan Solo and Terang Bulan, on the violin which they had with them. Then we sang Japanese songs to their violin music. The foreign students and we Japanese were comforting each other.

At night, we put up mosquito-nets on the school grounds and slept under them. For meals, we ate thumb-sized sweet potatoes, which were grown in the school grounds, after boiling them in an iron helmet on an firepit we built using stones, although they were rather young to eat.

How long were you together?

We spent a week together, from August 7 to 14.

I can never forget the beautiful stars we saw together on the roof of the university building on the night of August 7.

On August 8, we went to my family’s air-raid shelter to dig up food which my family had buried there.

I thought we could eat proper food after all this time. All we found there, however, were a kettle for the tea ceremony which had been heavily burned and deformed by heat, and black ash. Due to the location of my house, very close to the hypocenter, almost everything even in the shelter had been charred by heat at thousands of degrees Celsius.

To my happy surprise, while there, I met my mother, who arrived there to search for my father and me.

She thought I was a ghost when she saw me surrounded by the foreign students, because she didn’t know what was going on.

That night, my mother stayed with us.

She seemed to remind the foreign students of their mothers, and they happily called my mother “Mom,” like calling their own mothers.

Did you keep in touch with them after you parted on August 14?

Yes, I did. I exchanged letters with some of them after parting, and the letters I received are kept in Hiroshima University.

Didn’t any of the foreign students get any radiation effects?

Mr. Syed Omar, who was from Malaysia, fell ill on the train heading for Kyoto and died there on September 4 that year.

At Enkoji temple in Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, his gravestone stands facing to his homeland.

Other foreign students and I also suffered aftereffects from the A-bombing.

Any thoughts and messages to pass on

Lastly, would you tell us what you would like to pass on to the next generation?

I have been grateful to those foreign students from the bottom of my heart.

They always helped and supported us. We were comforted and encouraged by them.

When I told them, “I feel very sorry for you having such hardship in Japan,” they said, “It cannot be helped.” They never spoke ill of Japan and worked earnestly taking care of the injured all day.

We have to be kind to others and strong in any situation. We must not fight against others. I have learned a lot from those foreign students and through the A-bombing, even though it was a horrible experience.

War is nothing but murder. There must not be any war on the earth.

War involves everyone -- young ones, little ones and adults, and could break their hearts as well.

Peace is really precious.

I would be happy if my experience would bring home to many people how evil it is to produce and possess nuclear weapons.

Interviewed on June 2017.

About

"Interviews with HIROSHIMA memory keepers" is a part of project that Hiroshima「」– 3rd Generation Exhibition: Succeeding to History

We have recorded interviews with A-bomb survivors, A-bomb Legacy Successors, and peace volunteers since 2015.

What are Hiroshima memory keepers feeling now, and what are they trying to pass on?

What can we learn from the bombing of Hiroshima? What messages can we convey to the next generation? Please share your ideas.