HIROSHIMA memory keepers Pass down a story

Vol. 13 2018.7.25 up

You should always be aware of social problems as they affect you, then listen to the survivors' stories. Don’t be indifferent to politics, peace or poverty. This is necessary in order to have a dialogue.

Masayo Mori

A-bomb survivor

What do people handing down the experience of the A-bombing think and try to convey?

Ms. Masayo Mori, 92, taught Japanese for many years at Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior&Senior High School.

She told us what she thinks about peace education and what she wants to convey to young people.

Section

The opposite of “war” is “dialogue”

Is it OK that I will only answer your cont-ttl-qs today?

I’d rather have a dialogue with you than tell my story. I don’t want you to take a passive role.

Lately, when I tell my story to young people, they are so passive, which makes me discouraged.

I wonder why they come to Hiroshima and what problems they are interested in hearing about. I often can’t get what they want to know by listening to my story and what they feel or think after listening to my story.

I have no idea what my story means to their lives.

We’d love to have a dialogue.

Because young people have rare opportunities to hear the stories of war or the A-bombing in their lives lately, they must have feelings of ghoulish curiosity.

However, people listen to the survivors stories and only feel the A-bombing was very scary. I am afraid that it becomes mutual self-satisfaction to both story tellers and listeners.

I think it is meaningless to just get the impression that we should denuclearize.

You should always be aware of social problems as they affect you, then listen to the survivors' stories. This is necessary in order to have a dialogue.

I often think about what peace means. What do you think about peace?

I think the concept of peace is vague, and it is different, depending on the person. For example, people who are in a war now might think peace is a world without war, as it is said generally. However, people who suffer from domestic violence think peace for them is a home without violence. Because people have different values, there are many perceptions of peace.

Yes, peace is a very abstract word as you said. It’s a very difficult matter. I absolutely doubt that peace would come if war were abolished or domestic violence was solved. I think “dialogue” embodies “peace,” which is abstract.

What do you mean by “dialogue?”

I think the opposite of “war” is “dialogue.” Dialogue is different from debate. In dialogue, people respect each other and talk to each other with their own opinions.

Having a dialogue makes people recognize and accept their common and different values.

I believe that after having a dialogue, people can become aware of their new shared purpose. This is the ideal way to create a peaceful world.

Militaristic girl and the A-bomb experience

You entered Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior High School in 1937. Would you tell us about what those days were like then?

I think I was a militaristic girl.

The war had been continuing since I was born, and I naturally believed my life should be dedicated to our nation and Emperor. Discrimination against the Chinese and the Koreans was part of the general atmosphere.

Because our school was a Christian mission school and there were many American teachers, the Military and people called it an espionage school during the war.

I will never forget those hard times, being unjustly threatened and discriminated against.

What were some specific examples of threats and discrimination?

When I walked, little children threw sand at me saying, “You’re a spy!” Or a man on the street car looking at my school badge, said to me, “Are you a student of Hiroshima Jogakuin?

Quit such a school!” A meeting was held titled, “Abolish Hiroshima Jogakuin!” and its posters were put up around the city.

Religious teachers were summonned by the military and cont-ttl-qed like criminals. Finally they were forced to resign. Seeing those unreasonable incidents, I worked harder for the labor service of the country to show I was patriotic.

I’m 92 now and always wonder why I’m still telling my story to young people. Maybe because I lived during the war and want to convey my miserable experience.

Would you tell us your A-bomb experience?

I was working at the Compensation Department of the Army shipping headquarters in Inokuchi and was exposed to the A-bomb there on August 6, 1945.

In the middle of the morning assembly, a huge white light flashed for a second and the barracks shook with a tremendous roar. Thinking that bombs were dropped at close range, everyone rushed into the air raid shelters.

The following day, I went to Ujina from Inokuchi by boat to find my friends, and from Ujina I walked to the East Drill Grounds near Hiroshima Station. I saw many holes there. Many bodies were thrown into them and were being burned. Then, when I climbed up the stairs to Toshogu Shrine behind the East Drill Grounds, I saw many wounded people who had been brought and were lying shoulder to shoulder.

It was an insane world, not a human one. Seeing that scene, I had an indescribable feeling.

And because of the experience below, I have been telling my story.

A little girl, about five years old, crouching on the ground, reaching her thin arm with a small fragment of a broken roof tile in her hand, said to me, “Sister, give me some water, please!”

But I neglected her and passed by. After the war, going back to being a sensitive, ordinary 19-year-old girl, I couldn’t forgive myself and felt guilty all the time. Why on earth did I do such a thing! Why didn’t I have any emotion for her?

The fact that I abandoned her has been a scar in my heart.

One day I happened to see a news photo of the Son My Massacre during the Vietnam War, published in Asahi Graph. When I saw the photo of American soldiers smiling with a chopped head of a young Viet Cong, I thought their feelings might have been the same as mine that day.

They must have been good fathers or good neighbors, if they had not been in the battlefield. I understood that war made those ordinary people smile and lift up the head.

War is insane and it makes people inhuman.

In wartime, people lose their innate emotions and become inhumane.

They are even able to carry out ugly massacres. I think that is the fear of war.

Because of my experience, now I’m absolutely against war, though I was a militaristic girl at that time.

Did you have any physical problems after the A-bombing?

One month later, I had typical symptoms of radiation effects. Purple spots appeared on my body with a 40-degree fever. All of my body was swollen and rashes appeared. I got a knee scratch and it festered. Because the wound worsened and pus collected, my doctor drilled a hole at another place on my knee to get rid of it without anesthesia. Gauze was put in the hole every day to get rid of pus. Changing the gauze gave me a horrible pain.

War was standing at the end of the corridor

What do you think we can do to make indifferent people interested in themes such as war and peace?

That’s an important issue.

I think indifference is the most fearful thing. I myself experienced that the world around me had changed gradually. When I noticed, the war had already started.

There is a gloomy famous Haiku, “War was standing at the end of the corridor.”

It means that gradually the war sneaked into his house and when he noticed, the war was standing at the end of the dim corridor.

It’s too late when war starts.

War penetrates people’s homes little by little. Once it starts, nobody can stop it. So, that is what is frightening.

What do you think about current situations of the world? Do you have any issues that you’re concerned about these days?

Honestly speaking, I don’t spend my daily life being aware of what is going on around me. I think we are busy with our own lives and work, and don’t pay attention to other things.

That’s what I’m afraid of. I myself only vaguely felt the world was changing in a big way.

I’m afraid that I don’t think seriously about Japanese politics and wars happening in the world.

That’s the most fearful thing. I wrote the memoir of my war experience. Reading the story, you will see that I was born in February, 1926 and I lived in wartime from my young age till 19 years old unfortunately.

Yes, you really lived in a long wartime.

When you study about the war with these written materials, you get information about how Japan proceeded with it.

However, war is led by a nation. I think you should know how people were living in wartime: Were they happy or not? What hard times did they have? These historical backgrounds are also very important.

In particular, young people haven’t learned modern history.

I think emlearning from history will be necessary from now on.

In the book Till the War Started written by Yoko Kato, it says there were three opportunities for Japan to avoid the war. We have the history of having made a wrong decision.

I think we can learn from the history so we have a standard to judge when we face the same situation.

Young people might not have noticed, but I think this age seems very similar to the days before the war.

The reason why this old lady speaks out loud even now is that I want young people to cont-ttl-q Japan’s current situation, before it becomes too late. Because war will never be stopped, once it starts.

The way of Japanese thinking is to quickly forget the past and see the future as unknown.

Most people think only about their near future. So, I hope they learn from history and have a standard to judge things.

I’d like to tell young people how important it is to learn about war through its history, including different perceptions that each country has.

Accessible activity for peace

What do you think is an accessible activity for peace for individuals?

First of all, read books and get information to have your own words to express your opinion.

Secondly, you should be interested in politics. The voting age is 18 years old now. You should be responsibly informed when you cast your vote.

There are many books available. I think the number of young people who don’t like reading has been increasing. Are comics good enough to read?

Though there might be good comics, reading books is more important.

When you find words that move you, they become your treasure. By marking those words or writing what you think about them, you can have your own opinion and your mind is enriched.

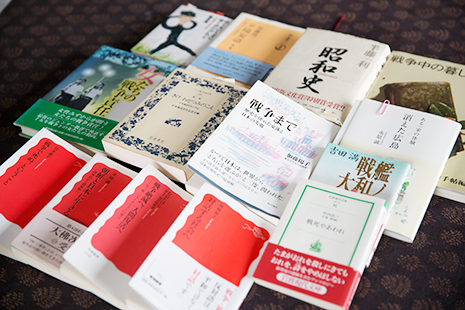

What books would you recommend us to read?

I recommend The History of the Showa Era written by Kazutoshi Hando.

It’s a very thick book and it takes a long time to read; however, it is worth reading.

You’ll be very interested in the history. Till the War Started written by Yoko Kato, which I mentioned before, was intended for high school and university students, so it is not difficult to read. Another one is Listen to the Voices from the Sea, letters written by Japanese student soldiers who died. You can see what they thought and how they died in the war.

Well, just studying war isn’t meaningful at all.

Please ask yourself if there is anything you can do. Please remember these three words: knowing, thinking and acting.

Thank you for telling us your important ideas today.

Interviewed on June 2018.

About

"Interviews with HIROSHIMA memory keepers" is a part of project that Hiroshima「」– 3rd Generation Exhibition: Succeeding to History

We have recorded interviews with A-bomb survivors, A-bomb Legacy Successors, and peace volunteers since 2015.

What are Hiroshima memory keepers feeling now, and what are they trying to pass on?

What can we learn from the bombing of Hiroshima? What messages can we convey to the next generation? Please share your ideas.